Analysis

The suspension of food aid to Tigray expected to kill innocent civilians

Published

3 years agoon

Last week the UN World Food Programme (WFP) and USAID both announced a suspension in food aid to Tigray, where an estimated 5.3 million people are known to be starving. While neither statements gave a timetable for when food distribution could resume, UN Resident Coordinator Susan Cozi told Tigray TV that the investigation was expected to continue until June at least. If food assistance remains suspended for the duration of the investigation, the consequences will be devastating for the people of Tigray.

The full impact of the suspension of aid is impossible to predict due to the unusual efforts taken by the United Nations and the Ethiopian government to suppress information about the current conditions in Tigray. The WFP has still not released the emergency food insecurity assessment that was conducted in February and the UN-IOM has released no official data about the conditions being faced by an estimated 2.5 million displaced Tigrayans. This data was being collected and reported during the conflict, but for reasons unknown, the “unfettered” humanitarian access promised in the Cessation of Hostilities agreement appears to have had an adverse impact on transparency.

There is even some confusion about when food distribution was halted. The initial report about the suspension of food aid did not come from the WFP or USAID, but rather from the Associated Press, which reported that the suspension was announced to partners on April 20. The official announcements from WFP and USAID came on May 3. On the same day as these announcements, the Director for the Tigray Early Warning and Food Security Directorate challenged the previously reported suspension date. In an interview with Tigrai TV, the head of Tigray’s Early Warning and Food Security Directorate Gebregzabiher Aregawi stated that the suspension actually began a week earlier on April 13. However, an unpublished food distribution dashboard update shared with Tghat Media from the week ending April 19 notes a “temporary suspension from 30 March to 14 April.” The update also reported that food was distributed to “some remaining IDPs” in Mekelle on April 15.

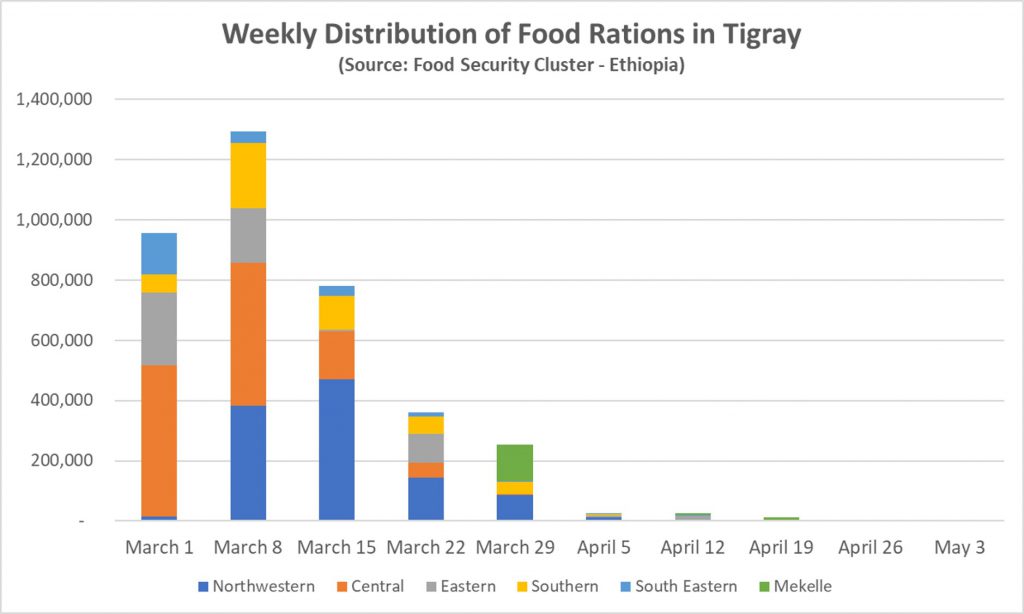

The food distribution data supports the initial report from the Food Cluster. As shown in the chart below, distribution fell sharply by 90% in the first week of April. The Food Cluster data for the week ending April 19 also shows that a total of 12,601 people received a food ration in Mekelle, which appears to quantify the reference to “some remaining IDPs.” Outside of the capital, only 52 food rations were distributed.1Unless otherwise noted, all food distribution data is derived from analysis of the Food Security Cluster – Ethiopia’s Weekly Food Distribution Dashboard, which can be found at https://fscluster.org/ethiopia/documents.

This data suggests that USAID and WFP quietly shut down food assistance to 5.3 million starving Tigrayans more than a month before any official announcements were made. As a result, when USAID and WFP finally announced the suspension, 94% of their collective caseload had already gone more than six weeks without any outside food assistance. As shown in the chart below, by May 3, only 315,528 food rations had been distributed in the past six weeks. If food assistance is restarted in the first week of June, which currently appears to be the best-case scenario, no one in Tigray will have received a food ration in the past six weeks and only 1% of the collective caseload will have received any outside food aid in the past ten weeks.

[CHART 2: 6/8/10 Rolling Totals]

As noted, it is impossible to even begin to predict how this new disruption of food aid will affect the people of Tigray because humanitarian agencies are not reporting on the living conditions of people on the ground. Since the resumption of fighting last year, only one report has used an empirical approach to collect information directly from Tigrayans. The study included focus group discussions with returnees in the Eastern zone of Tigray as well as site visits to several towns and villages. The findings confirmed some of the worst fears about the conditions on the ground in Tigray. The report was published in March and was removed by the UNHRC just days later with no official explanation.

The UN and other organizations have not always suppressed this kind of information from Tigray. From March 2021 to February 2022, the IOM performed emergency IDP hosting site assessments, which were made publicly available. Additionally, the WFP published Emergency Food Security Assessments in January and August of 2022. As illustrated in the following table, the findings of the August food assessment showed that Tigrayan families were barely surviving without much assistance reaching them.

Current Conditions in Tigray Demand a Localized Response

Less than a week after the last food assessment was released, fighting resumed between the Tigrayan and pro-government forces and continued for the next two months. During this period, humanitarian assistance coming into Tigray was blocked and pro-government fighters committed large scale looting and pillaging of everything from crops and livestock to personal property to critical infrastructure. This is in addition to the brutal violence committed against Tigrayan civilians which caused up to 2.5 million people, many of them farmers and herders, to be driven forcibly from their land before last year’s harvest. The impact of this mass displacement of farmers and herders on the already strained food system in Tigray has not been effectively assessed. Neither has the impact of the widespread looting and destruction of agricultural infrastructure, facilities, and equipment on Tigray’s food system been assessed.

Most of the Tigrayan families who fled the violence last fall remain displaced, away from their fields during the planting season, which will further disrupt the food system. Most of the damage that has been done to the agriculture sector of Tigray has not been repaired or replaced. A January report by Tigray’s regional Bureau of Agriculture and National Resources provides the only detailed scope of the damages to farms and irrigation available. The latest report from the Regional Emergency Coordination Council of Tigray indicated that aid agencies are still struggling to (a) provide basic agricultural inputs and (b) facilitate the return of displaced families.

To cut food assistance to Tigray now will kill innocent civilians. As cited in Michael Igoe’s recent article in Devex, the last FEWS report was clear: “At a minimum, food assistance must be sustained at current levels to prevent widespread hunger-related mortality and total livelihoods collapse.”

The suspension of food aid by USAID and WFP will facilitate “hunger-related mortality” and “livelihood collapse.” It should only be used as an absolute last resort. Unfortunately, over the past two years, cutting the humanitarian pipeline into Tigray has been the standard.

The preservation of human life in Tigray recommends a localized response to suspected diversion of food aid. The suspension of food aid will not include other regions in Ethiopia, nor will it include other countries in East Africa for very good reasons. These same reasons demand that the suspension of food aid is not extended to anywhere in Tigray where diversion is not suspected.

USAID and WFP should map out the locations where aid is believed to have been diverted or resold by beneficiaries. In areas where there is no evidence of diversion, food distribution should continue with better monitoring and oversight practices. In areas where there is evidence of diversion, food distribution should only be suspended until teams (like, for example, USAID’s Disaster Assistance Response Teams) can establish a temporary presence to oversee distribution and investigate the nature of the diversion. Additional measures could include:

- transitioning from a six-week ration to monthly distribution;

- reducing the number of food distribution points or adding distribution points closer to IDP hosting sites;

- establishing partnership agreements with local flour mills to serve beneficiaries who lack the means to mill the wheat they are given; and/or,

- building the capacity of WFP’s existing market monitoring systems to also monitor for aid diversion.

There are a number of options available to WFP and USAID that would minimize the impact of a new interruption of food assistance in Tigray. If every mitigation measure is impossible or impractical, WFP and USAID should explain why.

Moving Forward

This crisis should be a wake-up call for WFP and USAID to reform their policies and practices in Tigray. For more than two years, humanitarians operating in Tigray have performed their services heroically at great risk to their lives. Courage has unfortunately been lacking on the country level in Addis Ababa and more senior levels in the US and Europe where failures are hidden behind a wall of silence. Humanitarian access has been consistently deprioritized for more than two years while hundreds of thousands of Tigrayan civilians are believed to have died from starvation-related causes.

USAID and WFP are correct to investigate any suspected diversion of humanitarian assistance, but who is going to investigate USAID and WFP? The most recent Northern Ethiopia Crisis Fact Sheet from USAID indicates that the evidence of diversion of food aid first emerged in mid-March in the Northern Zone. This would have been precisely the time when food aid was most vulnerable to misuse. As the chart below shows, more than a million food rations were distributed in the Northwestern Zone during the first three weeks of March, which was more than the number of rations distributed in the first four months following the Pretoria Agreement. During the entire month of February less than 27,000 food rations were delivered in the same zone.

Without some very significant extenuating circumstances, this erratic pattern of food distribution would be considered a horrible practice due to the increased risk of diversion and misuse. So why did it happen? More importantly, how many people in areas like Sheraro, where diversion of aid was first uncovered, did not actually receive a ration and what is their current condition? According to the previously mentioned IDP site assessments, Sheraro once hosted 270,513 displaced Tigrayans in 20 sites spread throughout the district. Comparatively, about as many Tigrayans were displaced to Sheraro in 2021 as were displaced to the capital of Mekelle.

In Sheraro, the overwhelming majority (95%) of displaced Tigrayans were registered to six large hosting sites. Five of these six camps reported that the last food distribution had last occurred more than three months ago and all six reported that food assistance only reached a quarter of households or less. Also, five of the six IDP hosting sites reported that at least one child under five years old had been admitted into special care for “severe malnutrition” in the past three months. At two of the three largest sites, “Acute Malnutrition” was the primary health concern reported.

There was no access to healthcare for displaced families in Sheraro. According to the dataset, a quarter of IDP hosting sites reported that health care infrastructure and service was “mostly functioning,” but in reality, it was not. None of Sheraro’s 20 IDP hosting sites had on-site medical facilities and in 14 sites, the medical facilities were more than 20 minutes away. However, proximity was not the most important factor. All twenty sites in Sheraro reported that most people could not access the off-site medical facilities due to a lack of medicine and the cost associated.

At the time that the IDP hosting site assessments were being conducted, the country director of the WFP was outraged, but for the wrong reasons. In SA Omamo’s recent book “At the Center of the World in Ethiopia” he described his response to a claim made by former WFP Chief David Beasley on June 6, 2021 that people in Tigray were dying of hunger:

“Dying of hunger?! […] I called trusted staff in Tigray and asked them to do some informal checking. Was there any famine? Were people arriving at food distribution sites in very bad shape. Were there any stories of people dying of hunger? […] There was no evidence at all of anyone dying of hunger. None. Zero.” Omamo (2022), pp.59-60

The scope of Omamo’s “informal checking” is unclear, but it obviously did not include the IDP hosting sites in Sheraro, where children were most certainly dying of hunger. The subsequent food security assessment released in January 2022 also failed to include Sheraro, which was considered accessible, but was not directly sampled. Since the IDP hosting site assessments, virtually nothing has been revealed about the conditions faced by IDPs in Sheraro or the host population, other than the fact that enough food to feed more than 130,000 people was diverted.

Omamo’s forced resignation from WFP was mentioned in his memoir. While he declined to provide any details about any accusations being leveled against him at the time, it does not appear that his counterfactual denial of starvation in Tigray was the cause. WFP has not commented on his resignation or his erroneous claims.

For all the lack of clarity surrounding WFP’s activities in Tigray, four things should be obvious:

- WFP senior management have failed the people of Northwestern Tigray. The former country director’s job was to prevent starvation-related death in the Northwestern zone of Tigray. If he did not believe that people were dying of starvation in this zone, he could not have been effective.

- WFP has an obligation to investigate not only the diversion of food in Sheraro, but also the condition of the people in Sheraro for whom the food was intended. It is time for WFP to assess food insecurity in Sheraro, the failure to do so over the past two years is indefensible.

- WFP has a particular obligation to get food to the people of Sheraro. If the food distribution reported in March did not actually reach the people in urgent need, it means that they have not received food this year. This is no longer a humanitarian response, it is a rescue mission.

- WFP must adopt new standards of transparency to ensure that the world has some understanding of the conditions that human beings in Tigray are facing, and that some accountability exists at the highest levels to effectively relieve those conditions.

For the present moment, however, the suspension of food assistance in Tigray must be lifted, at least in areas where there is no evidence of diversion. The WFP and USAID must adhere to the doctrine of “do no harm.” If this suspension of food aid is allowed to continue until June it could easily become the catalyst for the next wave of mass starvation deaths in Tigray.

Amanuel Asgedom

May 10, 2023 at 1:18 pm

It is a bit stranger to hear such type of report from WFP. First of all since the November 4, 2020 tens of thousands of food and non food items were looted by the Eritrean, Amhara and ENDF. At this point WFP was reluctant and even remains silent to officially declared about this situation to the world. Similarly, one of it truck had been targeted by the Ethiopian drone damaged partly, still they don’t like to properly tell to the world. Its Mekelle office and similarly Adiss office is full of with people highly affiliated with the current politics.

When we come to the current report with regard to the division if resources it is still surprised me who WFP is as such lossless its levels of resources control and.verifications. As far as I know when WFP was selected to take responsibility on the distribution of food from USAID , there are different parameters that WFP shoul to fulfill. These are:

1) Qualified SV of the organization, person in charge such us CoP, Commodity director/manager, commodity management team both at national, regional as well as food distribution points, Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E), food distribution monitoring teams and so on.

2) Safety and security of food handling, storing and management.

3) Defined Standard Operational Procedures (SOP). This includes; (a) how to verify the registered beneficiaries reported by government. (b) Assigned staffs at food distribution points to verify if the eligible personal or officially delegated are colleted the food. (c) specifically, all aids are handed to the target beneficiaries by opening the package to discourage selling at market. And so on

4) Reports of diversion is expected to be declared when the first small incident are happened. Therefore, failure to report on time is making accountable to the budget holders. At this point WFP is ths first line accountable institutions in this regard.

Moreover, what is nor rational is, due to the failure of WFP, and may be government the needy people shouldn’t to be penalized. Otherwise, the last three years it was not only the food aid supports the IDPs and host community to withstand all the extraordinary siege, shock and food shortages. Rather, the lical community and diaspora had a lion share to assist them and yet continued.

Hope, the USAID will consider the situation of human right, that every individual havw the right to food access. It shouldn’t to follow the thought of “the fighting of two elephant suffered the grasses”.

Duke

May 10, 2023 at 6:08 pm

I agree complete with everything you’ve said except that I have found the Mekelle office of the WFP to be much more professional and helpful than the Addis office. That’s only my observation from the outside, I could be wrong. Everything else tracks. 🙏