“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” – George Santayana

In July this year, I went to Tigray for a visit. During my brief stay, I had a chance to see churches around Mariam Shewito, an area outside of Adwa, where the Eritrean Defence Forces had committed a massacre during the final weeks of the war in October 2022.

One of the churches I visited, Endaba Libanos Church, where some of the victims of the massacre were buried, is located in a valley near the town of Mariam Shewito. To reach the church, one has to walk off road crossing farm fields and farmers’ houses and a river that runs through the valley. As I passed through the villages, the signs of war were visible: looted and destroyed houses, burned farm stores, and stories of atrocities, displacement and destruction.

On my way to the church, I met a person who came from a nearby city to visit his family, and struck up a conversation on what life there was like during the war. He happened to know some of the victims and their families. While we were walking, he was pointing to houses scattered around, and recounting how each has lost family members. “Do you see that house?”, he says while pointing his finger to the direction of a house at the foot of a nearby hill, “three members of that household, a father and his children were killed by Shaebia [Eritrean soldiers]”. A little farther, another house, another family and another story of members killed by Shaebia, sometimes one or two, while at other times three or more members killed from the same households: it was easier to count the households that were not affected. Those killed included the elderly who witnessed the murder of their children in front of their eyes and begged not to be left alone, those who were sick and did not flee, and some unlucky ones who fled from other areas thinking it was safe. Eritrean soldiers did not spare the elderly, women, children, priests, or those with physical disabilities: everyone was a target.

After walking for more than half an hour, we parted ways , while he went to his family house, I continued my journey to the church. Except for three elderly mothers who were praying at the gate, the church was empty since it was a weekday and in the middle of the day. The head priest of the church was not around. Noticing that I was new to the area, one of the mothers, watching me compassionately and wondering why a city-dweller stranger was there, greeted me and asked why I was there. I explained myself and asked about how the situation was during the war. The mothers took their time to show me the graveyards of the people killed by Shaebia, pausing at every grave and crying and praying for the dead. The entire experience was so sombre and traumatic that at one moment I was regretting why I came to the church and asked them to reopen their wounds. More than forty people were buried in the church, some were identified as locals while others were not, since they did not have IDs or their bodies were not identifiable by the time they were discovered.

At the end of the visit, and before leaving the church, I asked the mothers if they had any experience from the past to compare what they had witnessed during the war. Judging by their grey hairs and their appearances, they seemed old enough to have lived through the eras of Haile Sellassie and Derg governments. They wandered through a mental journey down the memory lane of the past searching for an answer. And after a heavy and pregnant silence, one of the mothers replied, “there is none, even the Derg times were not as bad as these last three years”.

When I left the church, I was contemplating the weight of the conversation I had with the elderly mothers. And later as I continued my journey across Tigray, I came to realise that what I witnessed at Endaba Libanos Church is a microcosm of what happened in Tigray. As the report by UN International Commission of Human Rights Experts on Ethiopia (ICHREE) indicates Ethiopia and Eritrea as well as armed forces from the Amhara region have committed mass killings, widespread sexual violence, mass arrests, siege and starvation, and displacement and forced expulsion of Tigrayans. The massacres, siege, starvation and cultural genocide and the environmental damage and destruction of livelihoods of the people of Tigray has experienced in the last three years have no parallels in their history and are not comparable to any of the past atrocities carried out by successive Ethiopian governments. Though it is a continuation of longstanding genocidal under-currents that run deep through Ethiopian history, the Tigray Genocide is a unique and era-defining event, unprecedented in its magnitude and depth, and an event that has fundamentally changed the social and historical trajectory of Tigray.

Genocide happened, so what?

Although the legal determination requires further investigation, the available information suggests that Ethiopia and Eritrea have committed a genocide in Tigray. The critical question is how should Tigray respond: as a society fundamentally altered by the events since November 2020, what is the proper social, political and cultural response for this unprecedented evil in the history of Tigray? How should Tigray reimagine its social, economic, political and cultural relations with the states and societies that were determined to wipe it out from existence?

As Tigray emerges slowly, at individual level, people are finding different coping mechanisms to reckon with the ramification of the war and its aftermath: there is bewilderment, anger, regret and diverse attempts to account, make sense of and interpret events, normal reactions for a society that has yet to find closure to a genocide it has witnessed. These attempts include self-initiated measures to preserve the memory of massacres, rape, destruction and injustice, music videos, books, documentaries, paintings and artistic productions that are now becoming the reserve and sites of the cultural memory of the Tigray genocide.

However, as a political community and body politic, Tigray’s collective response has been lacklustre to say the least. This is a serious societal failure especially in a context where perpetrators of war crimes, crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing seem to be getting away with their crimes and their respective political actors engage in denial whereas victims are left to pick the pieces. So far, the Tigray Orthodox Church (TOC) remains the only Tigrayan institution to look at the abyss of genocide and make a decisive break from the churches and religious leaders that have endorsed a genocide on the people of Tigray. While the rest of Tigray’s institutions and actors, especially the political ones, have yet to learn to take a leaf from the TOC’s book, Tigrayans have a duty to ensure that the Tigray Genocide is properly investigated, documented, justice and accountability pursued and kept in the public memory. One way of achieving this goal is to commit to remember and declare the day the Tigray Genocide was officially launched as a national day.

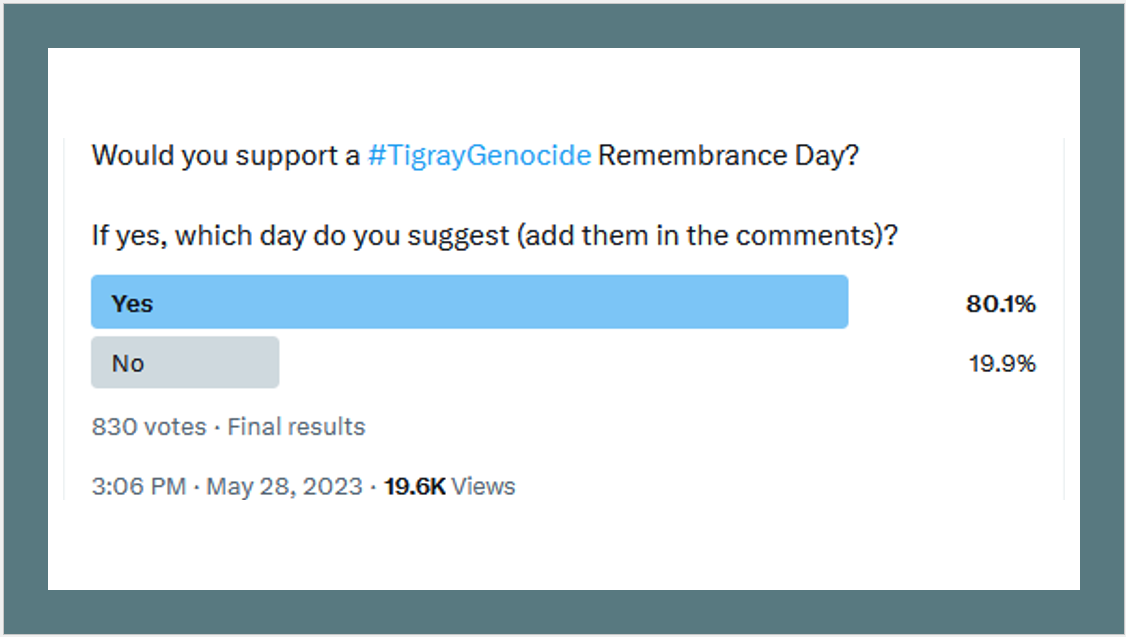

In May this year, I ran a poll on X (formerly Twitter) with the question: “Would you support a #TigrayGenocide Remembrance Day? If yes, which day do you suggest?”. More than 800 people participated in the poll, with 80% supporting the idea of having a remembrance day. The responses to the question “Which day?” are varied but with a clear majority suggesting “November 04” as a possible day of remembrance. As November 4th approaches, it is encouraging to see initiatives to remember the anniversary of the Tigray Genocide.

As the third anniversary of the war draws near, may we renew our commitment never to forget the Tigray Genocide and its victims, may we keep the memory and names of the thousands of children, women and elderly who perished in the war, and may we recognise the sacrifice and dedication of those who fell while defending their families and society.

Goyteom Gebreegziabher

November 2, 2023 at 6:07 am

Great summary you did it.

MULUGETA

November 2, 2023 at 2:22 am

This is a great idea. I had a similar idea except to be remembered monthly, በዓለ ትግራይ, based on the concept of the day of saints celebrated each month. For full info Here is my interview at TMH https://www.youtube.com/live/1eqQ53SQpg0?si=JdfxnpzaDbApeKX6